The Heuristic-Systematic Model

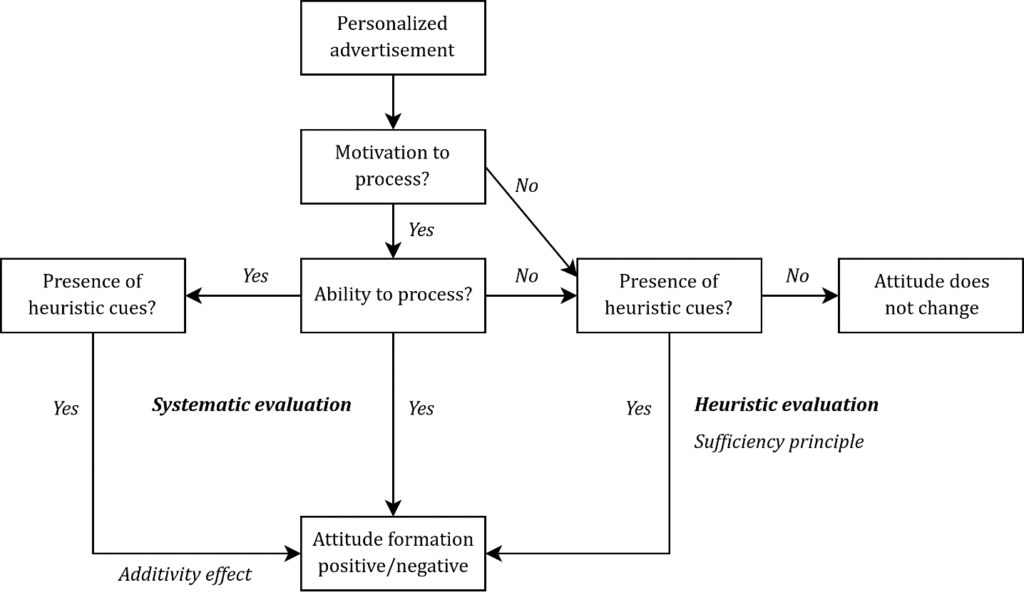

According to the Heuristic-Systematic Mode (HSM), people may take one or two modes—systematic processing and heuristic processing—to process a message, depending on different levels of cognitive ability (e.g., knowledge in the domain) and capacity (e.g., time constraint). On the one hand, in the case of systematic processing, people are likely to scrutinize the message analytically and form their attitudes based on the actual content (Chen & Chaiken, 1999; Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). On the other hand, in the case of heuristic processing, people make less cognitive effort to process the information, and they tend to form their attitudes based on heuristic cues (Chen & Chaiken, 1999).

The difference between the two modes is that the same communication variable, such as personalization elements, may influence people’s attitude-formation in very different ways. When people have enough cognitive ability and capacity, the communication variable will be scrutinized comprehensively. However, when the ability or capacity is low, only those judgment-relevant heuristic cues will be processed (Chen & Chaiken, 1999). In day-to-day life, people are “economy-minded” (Todorov et al., 2002, p. 196), and they tend to process information with the least effort (Chen & Chaiken, 1999). In other words, heuristic processing that requires less cognitive effort usually outperforms systematic processing (Chen & Chaiken, 1999; Todorov et al., 2002). People adopt systematic processing mode only when they have a strong motivation (Todorov et al., 2002). This reflects the sufficiency principle of HSM, which suggests that people will spend the minimum amount of cognitive effort to reach their goal of accuracy and confidence (Chen & Chaiken, 1999).

To apply this reasoning to personalized advertising, an ad that embeds individuals’ names may be more effective than a non-personalized ad because the personalized element serves as judgment-relevant heuristic cues. According to HSM (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993; Todorov et al., 2002), motivation is one of the key variables that determines which processing mode people will use. When a person has a strong motivation to process the subject of the message, he or she tends to spend more cognitive effort, processing all available information, and make a judgment based on thorough elaborations (Todorov et al., 2002). However, when a person does not have a strong motivation, he or she will arrive at a conclusion based on a few heuristic cues.

Applying the HSM framework and its sufficiency principle (Chen & Chaiken, 1999; Eagly & Chaiken, 1993), a high-involvement situation tends to increase a person’s motivation for issue-relevant thinking (Shang et al., 2006). However, people with a low level of involvement have a weak motivation and will spend less cognitive effort on attribute information, and they rely more on simple cues such as aesthetic product packaging (Reimann et al., 2010). In support of this notion, Axsom et al. (1987) found that the message’s argument quality influenced attitude at a high level of involvement. However, the attitude was more affected by heuristic cues (e.g., audience response as being enthusiastic or unenthusiastic) at a low level of involvement.

It is worth noting that HSM suggests that both heuristic processing and systematic processing can co-occur (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). An additivity effect can be expected if heuristic processing and systematic processing co-occur, in which case systematic processing does not override that of heuristic processing and both processing modes “exert independent and judgmental consistent effects” (Chen & Chaiken, 1999, p. 75). That is to say, people could engage in both processing modes simultaneously when they have strong motivation. In this circumstance, both the message content (e.g., argument quality) and heuristic cues (e.g., personalized elements) can be utilized to form a judgment. Several prior studies have empirically shown that the additivity effect occurs in a high motivation (or high involvement) condition (Chang, 2004; Maheswaran et al., 1992). For example, in Chang’s (2004) study (experiment 2), for high involvement products, both the assessment of product attributes (argument quality) and the country-of-origin information (a heuristic cue) exerted significant influences on the brand evaluation.

Figure 1 presents the HSM model, which embraces a “process-oriented” approach rather than a “variable-oriented” approach to persuasion.

Figure 1: Heuristic-Systematic Model for personalized advertising

The HSM also includes the hypothesis that attitudes developed or changed through the heuristic processing mode alone are less likely to be stable, less resistant to counterarguments, and less predictive of subsequent behaviors than attitudes developed or changed through the systematic processing mode (Chaiken, 1980).

References

Axsom, D., Yates, S., & Chaiken, S. (1987). Audience response as a heuristic cue in persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(1), 30-40.

Chaiken, S. (1980). Heuristic versus systematic information processing and the use of source versus message cues in persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(5), 752-766.

Chang, C. (2004). Country of origin as a heuristic cue: The effects of message ambiguity and product involvement. Media Psychology, 6(2), 169-192.

Chen, S., & Chaiken, S. (1999). The heuristic-systematic model in its broader context. In S. Chaiken & Y. Trope (Eds.), Dual-process theories in social psychology (pp. 73–96). The Guilford Press.

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers.

Maslach, C., Stapp, J., & Santee, R. T. (1985). Individuation: Conceptual analysis and assessment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49(3), 729-738.

Reimann, M., Zaichkowsky, J., Neuhaus, C., Bender, T., & Weber, B. (2010). Aesthetic package design: A behavioral, neural, and psychological investigation. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 20(4), 431-441.

Shang, R. A., Chen, Y. C., & Liao, H. J. (2006). The value of participation in virtual consumer communities on brand loyalty. Internet Research, 16(4), 398-418.

Todorov, A., Chaiken, S., & Henderson, M. D. (2002). The heuristic-systematic model of social information processing. The persuasion handbook: Developments in theory and practice, 23, 195-211.